Takeaways no. 93!

More in the body, less in the intro.

Enjoy!

If you'd like to support Teacher Ollie's Takeaways and the Education Research Reading Room podcast, please check out the ERRR Patreon page to explore this option. Any donation, even $1 per month, is greatly appreciated.

(all past TOTs here), sign up to get these articles emailed to you each week here.

A more effective approach to generating behaviour change, via @hfletcherwood

In this article, Harry explains two problems that hold us back from generating effective behaviour change through interventions, especially the sharing of successful practice. He then suggests a solution.

The two problems are as follows (my words):

- It’s hard to know what the active ingredient of an intervention is, because each intervention has multiple components

- Even if we know what the active ingredient/s is/are, we lack clear ways of describing it.

To this latter point, Harry explains it as follows:

We often use general terms: we talk about ‘trust’, ‘support’, ‘culture’ and ‘collaboration’. These are powerful influences, but uninformative terms. If a successful coach “built a collaborative culture,” what should we do to create the same culture? We must know what collaboration looks like, and how to encourage it: we must know exactly what the coach did, and what they asked teachers to do. A coach can share their approach with one colleague by having that colleague shadow them. But they cannot share their approach with a dozen colleagues, or multiple schools, in the same way.

So, what’s the solution?

Developing clearer language to describe exactly what is going on in an intervention! This is something that Doug Lemov and I spoke about in our ERRR episode and it’s something that Lemov has described previously as, ‘Shared language to describe technical aspects of an endeavour is one of the most underrated tools…'*

Luckily, as Harry points out, some progress is being made to this end:

Michie and her colleagues have addressed this problem by creating a taxonomy of behaviour change techniques. A behaviour change technique is an:

“Observable, replicable and irreducible component of an intervention designed to alter or redirect causal processes that regulate behavior; that is, a technique is proposed to be an ‘active ingredient’.”

MICHIE ET AL. (2013)

…

the team described each technique meticulously. For example, what’s the difference between making a plan and setting a goal? The Behaviour Change Taxonomy distinguishes between behavioural goals (going for a run) and outcome goals (losing weight). And it distinguishes between goals and action plans, because the latter must mention (at least one of) the “context, frequency, duration and intensity” of action: running at 6pm, daily, for thirty minutes, for example. Similarly, the taxonomy distinguishes between many forms of feedback: praise, feedback about behaviour, feedback about outcomes, feedback highlighting discrepancies between goals and behaviour, and so on.

Harry and his team are using this taxonomy to synthesise the literature on effective professional development. This is a really exciting initiative, so watch this space!

Read the full article here.

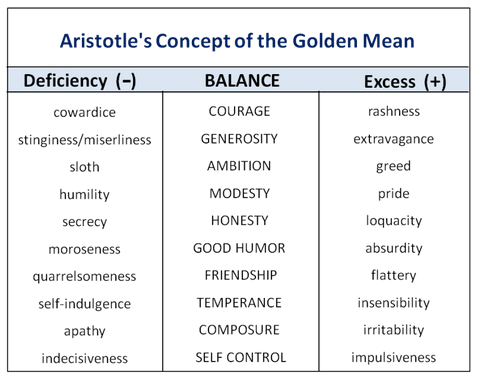

Desirable dispositions are a balance between two extremes, via @RethinkingJames and @GuyClaxton

This is the summary of an idea shared by Guy Claxton in a recent podcast with James Mannion. I really loved the idea. Essentially, it’s very similar to Aristotle’s idea of The Golden Mean, the idea that all virtues sit between undesirable extremes. Here are some examples (source)

Luke Tayler has captured this idea with the following seesaw diagram, based upon Claxton’s interview with James Mannion

Really enjoyed @GuyClaxton on @Rethinking_Ed. The idea of students needing to find a balance between pairs of dispositions is wonderful. Beware the false dichotomy!

My seesaw doesn't do Guy's ideas justice but I enjoyed making it, and it helps my thinking. Feedback welcomed ? pic.twitter.com/LsYB2K0WNM

— Luke Tayler (@geotayler) February 1, 2021

Rebuttal to, ‘Don’t teach skills, just teach knowledge', via @rethinkingjames and @rethinkingkate

An ERRR podcast discussion that I particularly enjoyed was with James Mannion and Kate McAllister on their book, Fear is the Mind Killer. Fear is the Mind Killer lays out a comprehensive map and philosophy for building independent learners. Within the book, they address many common arguments against teaching ‘learning skills’. Below is an excerpt from my summary for ERRR Patrons, which details James and Kate’s rebuttal to the argument that you can’t teach learning to learn.

…

The argument: You can’t teach Learning to Learn because knowledge is the source of all learning

Knowledge is the basis of all understanding. Higher order thinking skills, such as critical thinking, problem solving, and creativity, are fundamentally built on knowledge. For example, people think that master chess players are experts because they have developed the skill of thinking many moves ahead. Not so, they’re actually empowered to think fewer moves ahead because they’ve built up a vast knowledge base that allows them to simply recognise a board pattern or situation, then select from their knowledge bank an appropriate move to match the situation. For true expertise, teaching ‘skills’ is folly, we need to teach knowledge!

Daniel Willingham (whom also appeared on the ERRR) and E.D Hirsch are often cited in support for this argument. Hirsch's position on the importance of knowledge was in this podcast with Natalie Wexler.

The rebuttal: This argument (Knowledge first) isn’t wrong, it’s only half right

Firstly, this argument about learning skills is based upon the assumption that Learning Skills are devoid of knowledge, which is not true. James and Kate’s Learning Skills curriculum is full of knowledge. Some examples include:

- To effectively cooperate it’s helpful to know what effective talk-for-learning looks like. Students are supported to do this by being explicitly taught ‘talk rules’.

- For students to speak in a persuasive way, or give inspiring presentations, it’s helpful for them to have explicit knowledge of rhetorical devices such as anaphora, asyndeton, antithesis, hyperbole, and tricolon

- Explicit knowledge of Cognitive Load Effects can help students to overcome poor instruction themselves (more on this in my book)

Secondly, there’s significant research evidence that teaching learning skills, such as metacognition and self-regulation, are very useful indeed. The Education Endowment Foundation, a major education research body in the UK, places them at the top of their list of factors that positively impact learning, second only to feedback (see here or the Australian version). However, for a critique of the methodologies of this type of research – effect size based meta-analysis – see my discussion with Adrian Simpson).

Thirdly, James also pointed out an interesting paradox. Some proponents of a knowledge-only curriculum suggest that, ‘We all want students to have learning skills such as self-regulation, critical thinking, problem solving. But you don’t get this by teaching them directly, you get it by teaching knowledge, which then acts as the foundation for their independent learning’. James suggested this argument could be turned around, ‘We all want students to develop knowledge, but you don’t get knowledge by teaching it directly, you get it by teaching students how to learn, which then acts as the foundation for their knowledge building.’ Within the podcast, we then talked about the chicken-and-egg nature of these two ideas, and I suggested it’s more of a reciprocal relationship, at each stage, both some knowledge and some skills are involved, with each building on the other.

Finally, when people quote Daniel Willingham regarding the importance of knowledge, they often do so without including the quotes in their entirety. Willingham usually advocates for the development of knowledge in parallel with skills. Here are some illustrative quotes from his book, Why Don’t Students Like School?

‘facts must be taught, ideally in the context of skills’ …

‘The conclusion from this work in cognitive science is straightforward: we must ensure that students acquire background knowledge in parallel with practicing critical thinking skills’

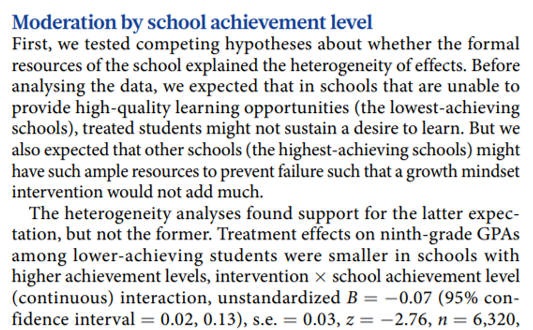

An online growth mindset intervention has a big effect, via @hfletcherwood

Original thread article here:

1) I have been very sceptical about growth mindset over the last few years, but a new study has substantially changed my mind…

— Harry Fletcher-Wood (@HFletcherWood) November 10, 2020

Below is the full thread from Harry

1) I have been very sceptical about growth mindset over the last few years, but a new study has substantially changed my mind…

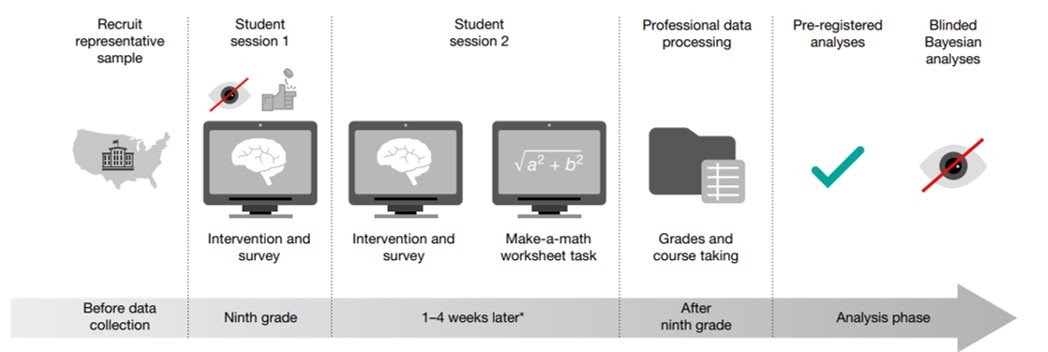

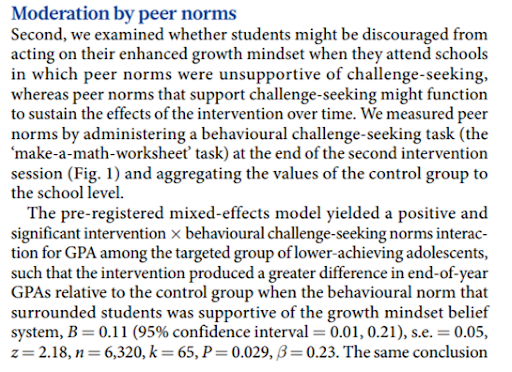

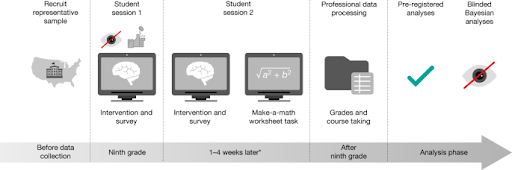

2) In research-design terms, this was bulletproof: pre-registered, randomly-assigned, teachers didn't know which students got the growth mindset intervention and analysis team didn't know the hypothesis or which group was which.

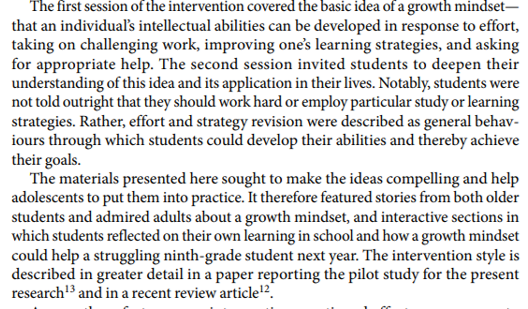

3) Students did 2 x 25-minute online activities about growth mindset: just telling them that we can get smarter (not telling them to practice). These were conveyed using various powerful techniques (like stories from role models).

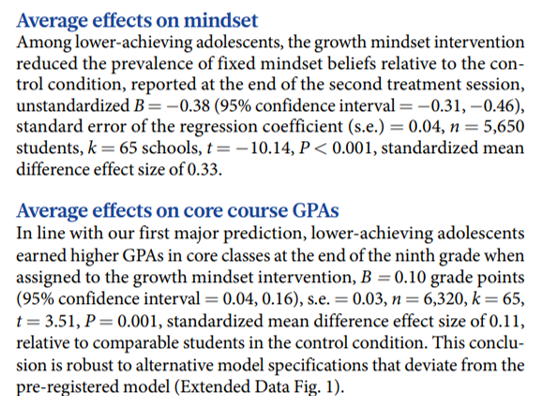

4) The impact: a) it changed students’ opinions about whether they could learn, b) lower-attaining students gained higher grades, c) students were more likely to choose more challenging maths courses the following year.

5) The intervention had less effect if the school was already effective (most students did well there), and if peer norms about achievement were negative.

6) I can't fault the study. Worth noting that this was designed by a stellar team – but it's scalable and powerful: 0.1 SD increase in GPA for an hour's intervention. So I'm having to update: growth mindset is more promising than I'd thought…

A national experiment reveals where a growth mindset improves achievement

Last tweet in the thread (Yeager et al., 2019).

A US national experiment showed that a short, online, self-administered growth mindset intervention can increase adolescents’ grades and advanced course-taking, and identified the types…

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-019-1466-y

Another working memory metaphor, via @F3Kpilot

It always excites me when people engage deeply in my recent book on Cognitive Load Theory in Action. What excites me even more is when they add to it in creative ways! I love the following library and librarian metaphor for long-term and working-memory, snipped from a longer summary/review of my book by @F3Kpilot.

Just finished reading your excellent book, Oliver! @ollie_lovell Here's a brief summary of Cognitive load theory.https://t.co/MamhD7xQlE

— Håkan Sjöberg (@F3Kpilot) January 31, 2021

Moving beyond, ‘Does that make sense?’, via Aaron Peeters

Last week in TOT we looked at Doug Lemov’s idea of, ‘Reject self-report’. One of the most valuable ways to reject self-report (which usually takes the form of vague questions like, ‘Got that?’), is to check for understanding, as was expanded upon in TOT092. However, in my podcast with Aaron Peeters, Aaron highlighted an additional way that this could be done. The following is an excerpt from my ERRR show notes that ERRR Patrons received to accompany my podcast discussion with Aaron:

give students a menu of actions after you’ve explained something. Instead of asking, ‘Does that make sense?’, you could give students a multiple choice selection such as. Would you like me to:

– Explain again but slower

– Explain again in a different way

– Repeat the explanation

– Write the key parts of the explanation down

– Go away, I get it, I’m ready to try it for myself!

This puts the student in the driver seat and boosts their agentic engagement.

This is still a form of self-report, so it should be used carefully, but it’s also a scaffold towards more independent learning. A question like this can scaffold the kind of monitoring and help-seeking that we hope to help students to begin to make automatic over time.

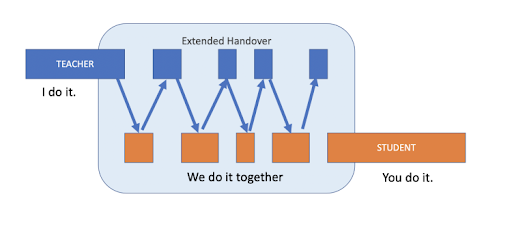

If your modelling isn’t working, maybe the handover isn’t long enough, via @teacherhead

In this article, Tom Sherrington pulls apart the idea of modelling, the I do, We do, You do, and provides a fresh perspective through a valuable metaphor of passing the baton without dropping it!

What is needed is a much more extended hand-over where the teacher works with the students to do the task together:

Zoom right in on that baton hand-over. It’s not instaneous; a crucial time passes when both people are holding the baton together. In that brief moment, they are communicating through the touch: Have you got it? No, not yet. Ok, I’m still with you. Grip harder. Have you got it now. Nearly, keeping holding, I’m nearly there.. Ok. You’re ready.. Off you go. Yes, I’m ready, let go. I already have…. you’re away.

What does it take to open a truly revolutionary school? Podcast via @rethinkingkate and @rethinkingjames

Kate McAllister and James Mannion are two of my favourite educators. This podcast is James interviewing Kate about her life journey (phenomenal!) and her recent efforts to set up an innovative school in the Dominical Republic! Ever thought… ‘I should do something about (issue x)' but never done something about it? Kate ACTS!!! This stuff is inspiring>

? New episode of #repod ?

Kate McAllister on opening a 'Hive school'

In this clip, Kate describes her philosophy of what education is, or should be, for.

Full episode: https://t.co/Dga7ssE0Cj pic.twitter.com/01oFJD8Q4e

— Rethinking Education (@Rethinking_Ed) February 2, 2021

Fantastic question-generating and auto-feedback-giving free maths resource, ht @mpershan

Wow. This is a pretty amazing website for maths teachers! Unlimited practice for students, plus structured feedback.

Watch at least the first 2 mins of this video. Thanks for the heads up on this one @mpershan https://t.co/bflCDlmxaK

— Oliver Lovell (@ollie_lovell) January 31, 2021

A mathemagical trick, via @mpershan

Just for a bit of fun…

Really useful range of information Ollie, presented in just the right amount for busy people. Snippets that I can use in my work with students, whilst training others and also in the therapy work I do. All change is learning.

Glad you find it helpful Georgina : )