Installment 94 of Teacher Ollie’s Takeaways. This week’s takeaways below. I hope you enjoy!

If you'd like to support Teacher Ollie's Takeaways and the Education Research Reading Room podcast, please check out the ERRR Patreon page to explore this option. Any donation, even $1 per month, is greatly appreciated.

(all past TOTs here), sign up to get these articles emailed to you each week here.

The Great Teaching Toolkit Evidence Review, via @EvidenceInEdu and @ProfCoe

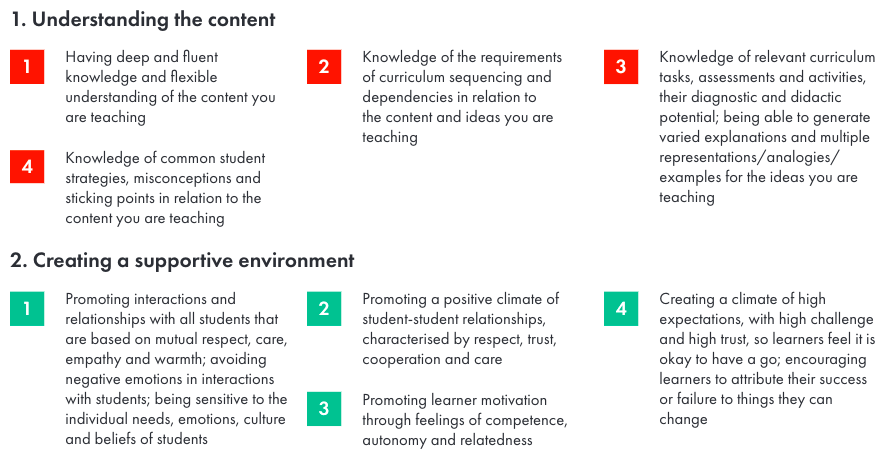

Evidence Based Education, a fantastic org made up of some of my favourite people working in education, has come out with a review of what is important for teachers to know and do in the classroom. They’re calling it the Great Teaching Toolkit. At first glance, it’s a powerful framework that captures the vast majority of important factors at play in the classroom. As a taster, here are the four key areas that it addresses:

- Understand the content and how it is learnt

- Create a supportive environment for learning

- Manage the classroom to maximise the opportunity to learn

- Present content, activities and interactions that activate students’ thinking

I’ve only had a cursory look so far, but I’ll be incrementally reading it over the next weeks and months, and will share key takeaways here in TOT!

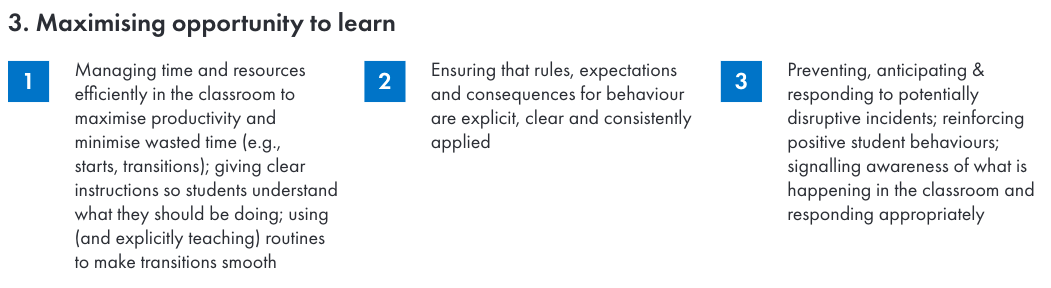

For a bit more of a taster, here are the 17 elements that the Toolkit currently explores, broken down into the 4 headings from above.

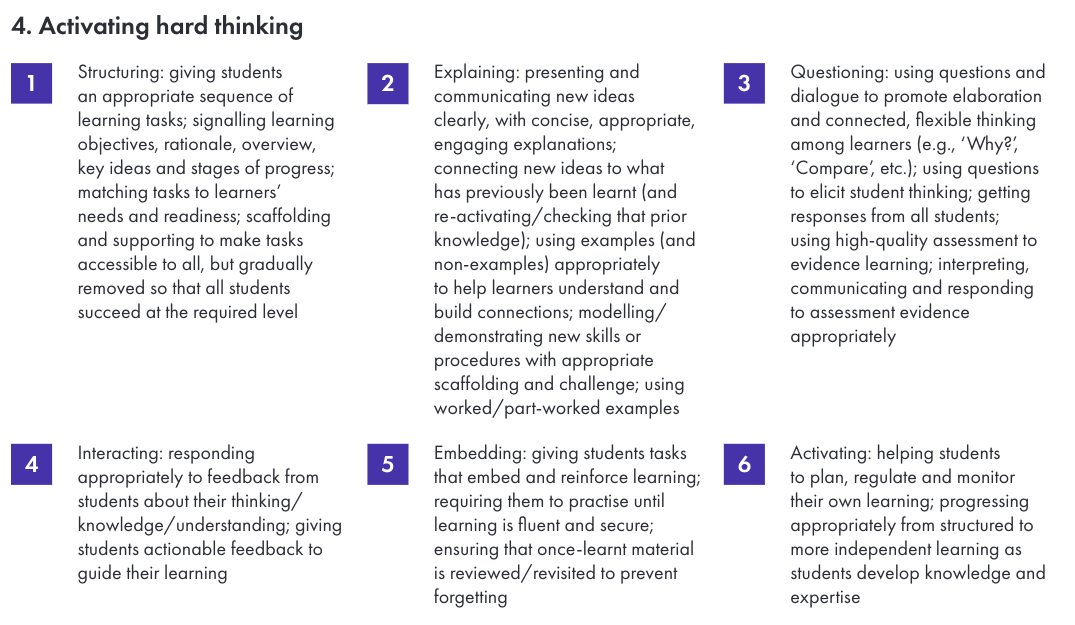

Leading and evaluating implementation with Guskey’s pyramid, via @tguskey ht @RethinkingJames

Implementing change in schools is hard, and it’s an area that I’m getting increasingly interested in. One of the people who is right across this issue is James Mannion, and I had the opportunity to hear him talk about it a few months ago. Here’s one of my takeaways from that presentation.

Guskey’s pyramid maps out five levels at which we can (and should) evaluate professional development (CPD in the UK). This can help us get a sense of how impactful our attempts at improvement are, and overcome some of the barriers to effective implementation that are often overlooked.

Level 1, Initial reactions: Did people enjoy the professional development? Were they comfy and did they have fun? Was the food good?

Level 2, Participant learning: Did people’s knowledge change as a result of the PD? This is a key precursor to other things changing.

Level 3, Organisational support for change: This level moves beyond the individual and asks questions like, ‘Is the organisation that the participant is going back to actually ready to implement this change?’ This is where the impact of PD usually gets stuck.

Level 4, Effective use of new knowledge and skills: This one builds on the prior levels. If, during the PD, participants had fun, learnt something, and don’t face any organisational barriers to implementation when they return to their school, they can go on to actually change their actions.

Level 5, Student outcomes: If we play our cards right, we’ll have the intended outcome of changing student outcomes (academic, socio-emotional, etc). This is, in most cases, the ultimate goal of teacher professional development.

To me, Guskey’s pyramid is a helpful tool to reflect upon how much impact we’re having with our PD, and where that impact may be getting blocked along the way.

For more on Guskey’s five levels, see here.

Improving students’ learning dispositions, a quick idea, via @GuyClaxton

When we’re trying to support students to strengthen their learning dispositions (things like their curiosity, attention, and determination), ipsative assessment can be a powerful way to do this. Here’s a definition of ipsative assessment.

Ipsative assessment – gauging progress in terms of personal progress and improvement, rather than comparing performance against fixed benchmarks (criterion-referenced testing) or against a population of peers (norm-referenced testing) – is much more effective at promoting pupil engagement and improvement than any kind of summative testing.*

During our recent ERRR podcast discussion, Claxton suggested an inspiring way that we can do this. Initiate a discussion with a student about one of their learning dispositions, such as their resilience. Have them talk about some instances in which they’ve demonstrated it, and how they think they’re going. Then ask,

Okay, janella, that's really interesting. Let's just leave that there for the moment. And let's just say, for the sake of argument, let's call where you are in terms of developing your resilience, what you've just described to me, let's call that four, could we now have a conversation about what five might look might be? What would five look like to you?

Here, numbers have been used as a bogus indicator of where we’re trying to get to! This could be a great little technique to help students, or even teachers during coaching, to evaluate where they’re at, and how to get to the next level.

*See the classic paper by Terry Crooks, The Impact of Classroom Evaluation Practices on Students, 1988, Review of Educational Research, 58(4):438-481 (source)

What to do with your eyes in the classroom, Track, don’t watch, via @doug_lemov

The following is an excerpt from my summary of my podcast with Doug Lemov produced for Patrons

TLAC Technique 4: Tracking, not watching

Summary: Be intentional about how you scan your classroom. Decide specifically what you're looking for and remain disciplined about it in the face of distractions.

In TLAC 3.0 this will be called, Active observation.

The key idea here is that the teacher walking around the classroom should be seen as a method of collecting objective data. This requires having clarity about what you’re looking for. Don’t just scan to ensure that students are writing, actually look at what they’re writing to ensure that they’re on the right track!

Related to this, Doug emphasised the impossibility of taking, ‘mental notes’ whilst going around the classroom (especially for early-career teachers), and stressed the importance of being clear about what you’re hunting for, then making notes about which student responses, or types of responses, you want to comment upon or refer to when you bring it back to whole-class teaching. Tracking = writing it down.

Two timing traps. Relevant in career and learner independence, via Cal Newport + Ollie

I recently finished Cal Newport’s So Good They Can’t Ignore You. Here’s one of my takeaways in relation to quitting your day job to take more control over your work life (it also has implications for education if you stick with me!)

Control (autonomy over your work and schedule) seems to be a vital ingredient to a fulfilling career, but there are two control traps. The first is getting control too early, when you don't have sufficient career capital to go it alone. The second risk is getting too much career capital such that you end up in golden and societal/expectational handcuffs that act as a barrier to you seeking the control now that you’re ready for it (e.g., your boss values you a lot and is willing to pull out all of the stops to keep you!)

A parallel here could be drawn to independent learning and student choice. We can make the mistake of giving students too much choice and autonomy too early when they don’t yet have the skills to effectively make the most of that choice. The second trap is waiting to late until students have spent too long in their, ‘long apprenticeship in learning how to be taught’ (Claxton on the Rethinking Ed podcast), are therefore very good at ‘studenting’, and are faced with high-stakes end of school exams where to change now would entail really big risks.

Both in schooling and career independence, freedom and empowerment comes from passing ownership into the hands of the individual. But timing is crucial!

Visiting a university campus in 8th grade influences grit and college aspirations, via @ehswanson, ht @DTWillingham

This study reports on an interesting experiment in which year 8 students were taken to a university campus three times throughout the year. Abstract below:

We study whether visits to a college campus during eighth grade affect students’ interest in and preparation for college. Two cohorts of eighth graders were randomized within schools to a control condition, in which they received a college informational packet, or a treatment condition, in which they received the same information and visited a flagship university three times during an academic year. We estimate the effect of the visits on students’ college knowledge, postsecondary intentions, college preparatory behaviors, academic engagement, and ninth-grade course enrollment. Treated students exhibit higher levels of college knowledge, efficacy, and grit, as well as a higher likelihood of conversing with school personnel about college. Additionally, treated students are more likely to enroll in advanced science/social science courses. We find mixed evidence on whether the visits increased students’ diligence on classroom tasks and a negative impact on students’ desire to attend technical school.

Dan Willingham’s tweet that alerted me to this study:

Visiting a college 3 times during 8th grade impacts students attitudes & intentions about higher ed, course selection in 9th grade (open) https://t.co/Uso4Xmp2Sz pic.twitter.com/kOoTnh1aTW

— Daniel Willingham (@DTWillingham) February 8, 2021

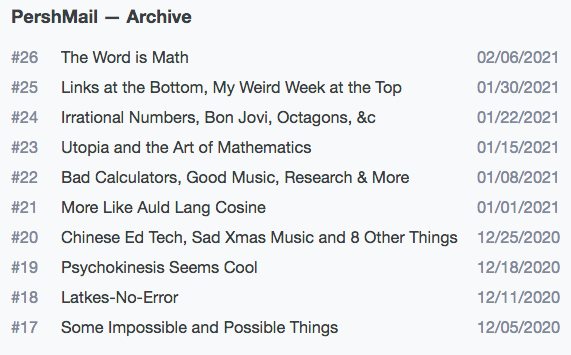

A new mailing list you may be interested in, via @mpershan

Click here for the mailing list.

Do we teach students the right kind of maths in school? Via @DamaniaLab and @StevenDLevitt

This week I came across the following funny tweet.

Truth! pic.twitter.com/vYoYFzt57N

— Blossom Damania ????? (@DamaniaLab) February 7, 2021

It got me thinking, once again, about a topic that I hadn’t thought of in a while, the maths that we teach students in school.

Is it really the most valuable thing that we could be doing with their time? Is the emphasis of the maths curriculum really in the right place?

The tweet prompted me to revisit a fantastic podcast on this topic by Steve Levitt.

I strongly suggest checking this podcast out. I’ll be exploring this issue, and writing more on it, in future.

A bit of fun, Action movie kids! Via @ActionMovieKid

Welcome new followers. Ya, it’s like this every day. Consider our channel: https://t.co/iEwwzETr8j pic.twitter.com/fFMsgubFB6

— ActionMovieDad (@ActionMovieKid) February 4, 2021