A long time between drinks but here’s Teacher Ollie’s Takeaways number 110!

I hope you enjoy it : )

If you'd like to support Teacher Ollie's Takeaways and the Education Research Reading Room podcast, please check out the ERRR Patreon page to explore this option. Any donation, even $1 per month, is greatly appreciated.

(all past TOTs here), sign up to get these articles emailed to you each week here.

First rate example of primary curriculum planning, via @EminaMcLean

I absolutely loved watching this presentation by Emina McLean about what’s going on in the curriculum planning space at Docklands Primary. If you want to see what quality primary curriculum looks like, look no further!

Wow!

If you want to see what rigorous and ambitious curriculum planning looks like, you have to watch this from @EminaMcLean, hosted by @ThinkForwardEdu. https://t.co/vfbasm7mtJ

It's all amazing, but it gets particularly juicy from about the 25 minute mark. pic.twitter.com/p3EypAC4fi

— Oliver Lovell (@ollie_lovell) April 19, 2022

Improve assessment by increasing the size of your ‘negotiated assessment domain’, via @Smithre5

In this great blog post, Reid Smith writes about how, with too much individual teacher autonomy over curriculum, we end up with conversations like this:

“I didn’t teach addition of fractions involving different denominators. Can we get rid of that question?”

“My kids wouldn’t be able to work out the fractional amount of a whole from a worded question.”

“I spent a fair bit of time on ordering mixed numbers – let’s add a question about that.”

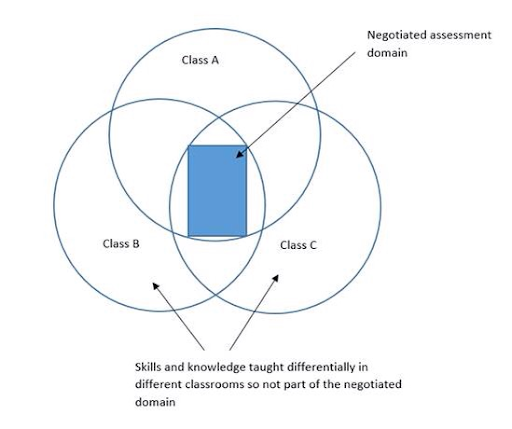

And a ‘Negotiated Assessment Domain’ that looks like this.

This means that much of the curriculum gets missed in both teaching and assessment. Not good.

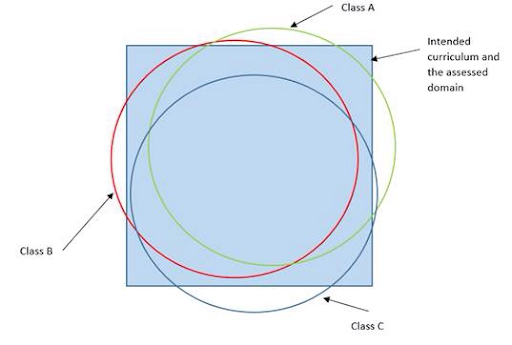

Smith argues that we should move towards a model that looks like this:

This can be done by specifying our curriculum in more detail (see Takeaway 1 from this week), or by changing assessment processes (e.g. writing the assessment and having teachers commit to it prior to the unit, or having an experienced external writer create the assessments in such a way that both students and teachers don’t see them beforehand).

I think that the idea of the ‘negotiated assessment domain’ is very useful, and I’m sure I’ll refer to it again in future.

How to teach students to better evaluate the credibility of digital content, via Sam Wineberg, ht @greg_ashman

One of the studies that I featured in Tools for Teachers featured Sam Wineberg’s work in determining what it is that expert fact checkers do that enables them to more quickly and more reliably check the credibility of digital content. It turns out that what they do is ‘lateral reading’, i.e. checking out the credibility of the source, rather than ‘vertical reading’, which is focussing on the content of the given article.

This new study shows that this skill was successfully taught to highschool students over six sessions. Very exciting news in our post-truth world!

Lateral reading on the open Internet: A district-wide field study in high school government classes. – PsycNET https://t.co/MmO1bNxLG9

— Greg Ashman (@greg_ashman) April 18, 2022

Put a box on the board for students to add their homework queries to, via @greg_ashman

‘I have a box on the whiteboard where students can write-up homework queries at the start of the lesson or add a tick to a query someone else has raised. Usually, the same question causes problems for several students and so I can tackle them with part of the class as the other students work independently.’

A great idea! From this article…

NEW TODAY Five minutes is a long time — Advice I give my students https://t.co/kJe4BkRY7H #aussieED #ukedchat #edchat #education #edreform

— Greg Ashman (@greg_ashman) April 16, 2022

Greg also says he’ll be blogging about how he teaches maths soon, so watch this space!

Maybe autonomy isn’t all it’s cracked up to be, via @jrsmcintoshNI

Full thread here.

It’s an interesting read.

Here are two stimulating tweets from the thread:

12. Choice is not in and of itself the thing that motivates or empowers us.

What matters is whether a particular set of choices empowers us to achieve a desired goal (A great paper on this: https://t.co/SUmHiOsEv1)

— John McIntosh (@jrsmcintoshNI) April 14, 2022

17. It may be better to pick out different human needs that each of the definitions identify, and ask whether these are being met. A manager might ask themselves:

– Am I supporting people to

○ Feel competent?

○ Feel heard?

○ Self-attribute success?

○ Understand?— John McIntosh (@jrsmcintoshNI) April 14, 2022

Everything you need to know about psychedelics and mental illness, via @StuartJRitchie

The potential benefits of psychedelic drugs has been getting a lot of press in recent years. This is a great, down to earth article by Stuart Ritchie pointing out some of the potential challenges and limitations to this research.

I took away three main arguments from this article:

- There’s a lot of motivated research going on (psychedelic aficionados and companies driving it)

- Some legitimate research is being exaggerated by its own authors

- There are large methodological challenges with doing good research on psychedelics, because participants very quickly identify whether they’re in the control or the experimental group, and this can bias their reporting of results (this is called ‘compromised blinding’, i.e. the participants aren’t really blind to their treatment)

For anybody interested : )